Research from several different fields has provided evidence of the criticality of early childhood in the development of the brain and its skills. Ninety percent of the development and growth of the brain occurs by the age of 6 years (Karoly et al., 1998). Blair (2002) called it a period of plasticity owing to its influence on an individual's personality through his/her life. Doherty (1997) identified certain crucial periods, within the first six years of life, in which brains are wired to respond to appropriate stimuli. If this stimulation is provided, it aids the development of advanced neural structures. Early experiences therefore have been proven to have a far-reaching impact on brain development as well as behaviour. Young (2007) propounded that diverse experiences impact the brain’s wiring and architecture and the physiology of the human body. All these contribute towards the attainment of emotional, cognitive and social outcomes.

In our context, the recently launched National Education Policy (2019) by the Government of India, is based on this brain research and emphasizes the criticality of high-quality early childhood education and its repercussions for the development of human capital in India. Aligning with the new policy, we adopted the International Early Years Curriculum (IEYC) in 2019, intending to aid brain development while children lead their own learning. The IEYC’s units, themes, and activities opened our world to new possibilities. We experienced it as the right blend of structure and flexibility for our contextual needs.

We devised ‘The Healthy Planet Way’ to implement the IEYC seamlessly across curricular areas of each year group. We based our approach on Harvard’s research on brain development (CDC, 2016) which states -

Brains are built over time, from bottom to top.

Brains work in ‘serve and return’ relationships.

Cognitive, Social and Emotional abilities are inextricably intertwined.

The Healthy Planet Way combines the above tenets through -

Learning Circles that help us provide stimulation for neural connections in young children.

Learning Conversations that support ‘serve and return’ during experiences.

Learning Gardens which combine social, emotional, and cognitive wellbeing.

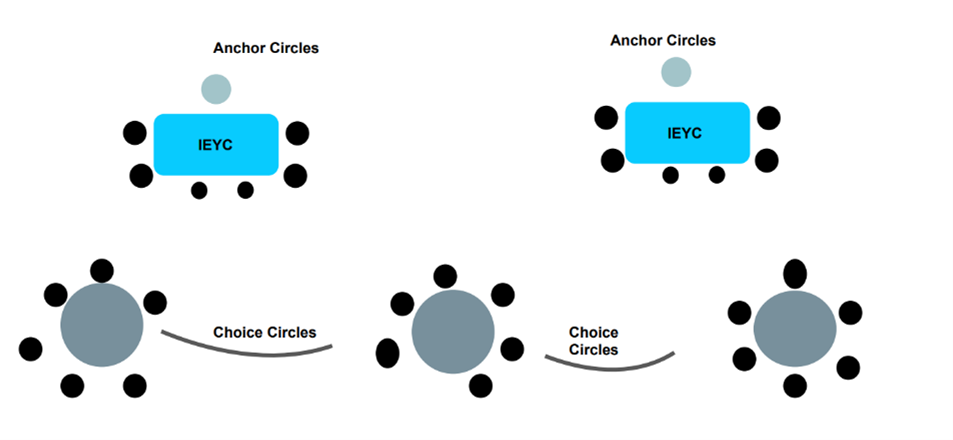

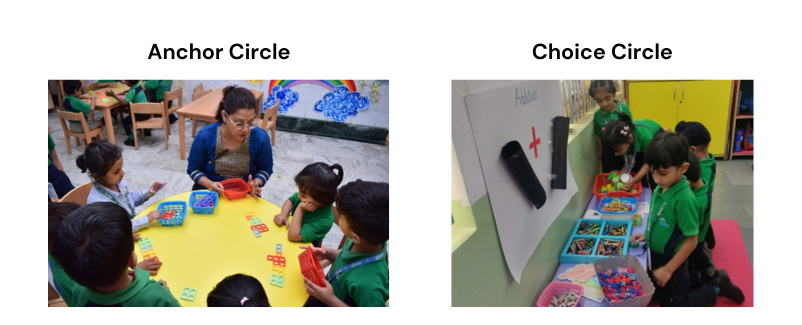

Drawing on social constructivism by Vygotsky (1962) who emphasised that children learn through interactions with others and their environment, our Learning Circles is a classroom setup that has facilitator-supported Anchor Circles, along with independent work on Choice Circles, where peers support each other, without an adult. All the circles engage in different IEYC experiences. While in Choice Circles children choose and move freely between experiences, in Anchor Circles our facilitators choose small groups of children to work with.

This approach allows children to lead their learning while interacting with each other and engaging in experiences of their choice. The adults are referred to as facilitators but essentially, are co-learners in the group, asking questions, and modelling learning behaviours. The process of learning takes precedence and facilitators observe and record children’s journeys.

The Anchor Circles are also useful for integrating literacy and numeracy goals with IEYC activities. Additionally, the entire process of moving through the circles supports the development of the IEYC personal goals.

A whole group discussion of an explore, express, and extend activity starts the Learning Conversations in the class. These conversations provide us with the opportunity to implement IEYC learning links, language opportunities, and reflective questions (Fieldwork Education, 2022). These conversations are intended to pique curiosity, and engagement and make connections to the real world. While children are stationed at the Anchor Circles, facilitators further these Learning Conversations. Involving all children in conversation was previously a challenge, but implementing the IEYC through these flexible Learning Circles has enabled our school to enhance children’s agency and expand the IEYC’s scope to be the foundation of all learning in the early years.

The physical environment of a class is regarded as the third teacher and greatly impacts the quality of early educational experiences (Gandini, 1998). Learning Gardens are our outdoor spaces that provide different settings for the IEYC experiences to extend from knowledge toward skills and understanding. Playing and learning in nature go hand in hand (Chawla, 1998), and free exploration and personal discoveries in nature spark curiosity (Higgins, 2002). Using the IEYC enabling environment guidelines, different outdoor spaces are curated to combine the benefits of outdoor play with the unit’s learning.

In conclusion, the IEYC has solved for us the challenge of ensuring active learning, curiosity, and engagement in our early years’ classrooms. The learning experiences allow for not only play but also enable reflecting, practicing, questioning, experiencing, and evaluating. Such a classroom addresses varying abilities, interests, and needs as well as encourages higher-order thinking in students (Tomlinson, 2000). We hope we are setting the stage for children to begin metacognition. The IEYC helps us move closer to our vision of enabling children to be active agents in their learning.

Learn more about the International Early Years Curriculum

References

Blair. C. (2002). School readiness: Integrating cognition and emotion in a neurobiological conceptualization of children's functioning at school entry. American Psychologist, 57 (2), 111-127. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.57.2.111

Chawla, L. (1998). Significant life experiences revisited: A review of research on sources of environmental sensitivity. Journal of Environmental Education, 29(3), 11-21.

Cosgrove, M. S. (1992). Inside learning centers. Retrieved October 23, 2022, from ERIC database

Doherty, G. (1997). Zero to six: The basis for school readiness (1st ed). Canada: Human Resources Development Canada. Retrieved on 25th July, 2023 from http://citeseerx.ist. psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.119.1467&rep=rep1 &type=pdf

Fieldwork Education (2022) International Early Years Curriculum Guide 2022-2026. International Curriculum Association.

Gandini, L. (1998). Educational and caring spaces. In C. Edwards, L. Gandini, & G. Forman (Eds.), The hundred languages of children: The Reggio Emilia approach-advanced reflections (2nd ed., pp. 161-178). Norwood, NJ: Ablex.

Higgins, P. & Nicol, R. (2002). Outdoor education: Authentic learning in the context of landscapes (Volume 2, p.4 foll.). Kisa:Sweden.

Piaget, J. (1977). The Language and Thought of the Child. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Karoly, L. A., Greenwood, P. W., Everingham, S. S., Hoube, J., Kilburn, M. R., Rydell, C. P. & Chiesa, J. (1998). What We Know and Don’t Know About the Benefits of Early Childhood Intervention. Rand Corporation: Santa Monica, CO. Retrieved 21st August 2023, from https://www.rand.org/pubs/monograph_ reports/MR898. html

Ministry of Human Resource Development, (MHRD, 2019). The Draft National Education Policy. New Delhi, Government of India. Retrieved on 08th June, 2023 from: https://mhrd.gov.in/sites/ upload_files/mhrd/files/Draft_NEP_2019_EN_ Revised.pdf

Ministry of Human Resource Development, (MHRD, 2020). National Education Policy. New Delhi, Government of India. Retrieved on 20th July, 2023, from: https://www.education.gov.in/sites/upload_files/mhrd/files/NEP_Final_English_0.pdf

Tomlinson, C. A. (2000). Differentiation of instruction in the elementary grades. ERIC Digest. Retrieved October 27, 2022, from EBSCOhost database.

Young, M. (2007). Early Child Development, From Measurement to Action: A priority for Growth and Equity. Washington DC: The World Bank.

Vygotsky, L. (1962) Thought and Language. Cambridge. MA: MIT Press.

Center on the Developing Child. (CDC, 2016). From Best Practices to Breakthrough Impacts: A Science-Based Approach to Building a More Promising Future for Young Children and Families. London:Harvard University. Retrieved on 27th August 2023, from https://46y5eh11fhgw3ve3ytpwxt9r-wpengine.netdna-ssl. com/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/From_Best_Practices_to_Breakthrough_ Impacts-4.pdf